Podcast: Play in new window | Download

Subscribe: RSS

Rundown

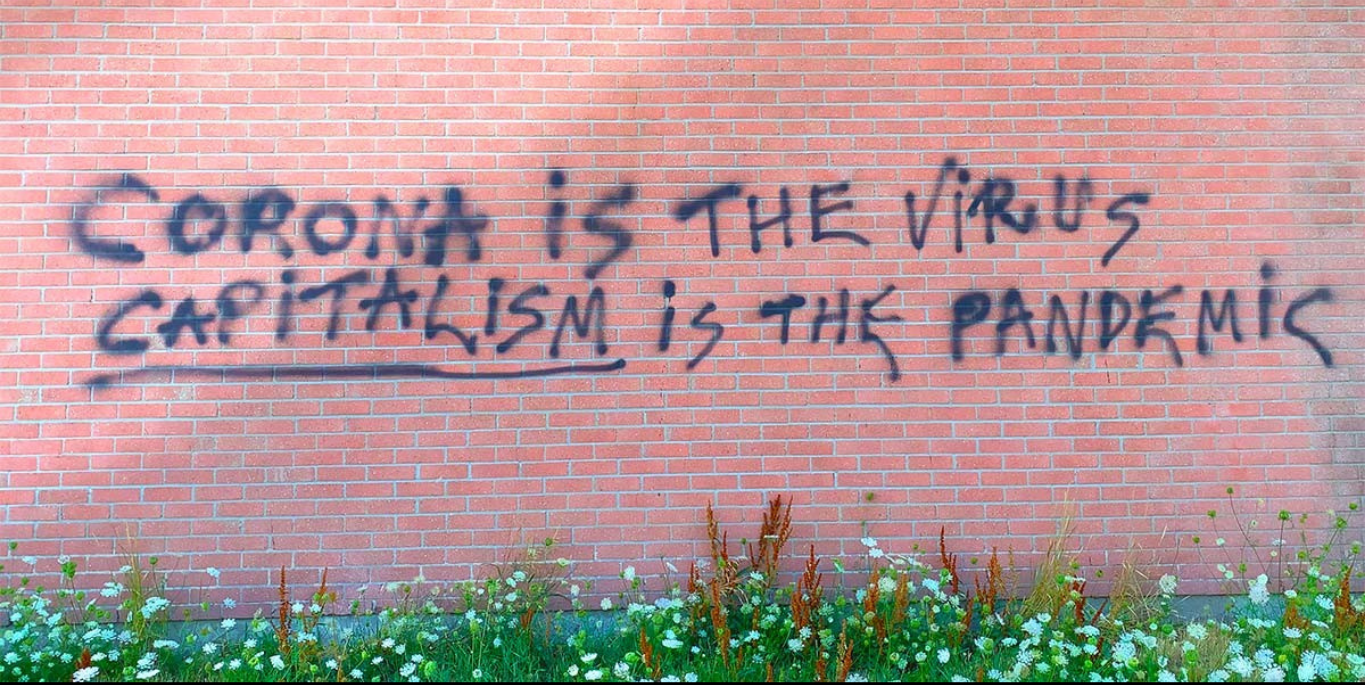

Mexie talks with Marxian economist, Dr. Richard Wolff, about COVID-19, the current economic recession, and the prospects for a post-capitalist future. Prof. Wolff argues that democratizing our workplaces from the ground up is critical to building that future.

Sources and Links

- Democracy at Work: https://www.democracyatwork.info/

- Democracy at Work on YouTube: https://www.youtube.com/c/democracyatwrk/

- Prof. Richard Wolff on YouTube: https://www.youtube.com/c/RichardDWolff

Support the Show

Transcript

F1: [MUSIC] How can we not only discover more compassionate relations with human beings but how can we develop compassionate relations with the other creatures with whom we share this planet?

F2: There’s an us before the wound, there’s an us before oppression, and to me pleasure is the way that we tap down into that.

F3: We live in capitalism. Its power seems inescapable. So did the divine right of kings.

MEXIE: Hello everyone, welcome to the Vegan Vanguard. It is Mexie and as promised, I am releasing my series of talks with Dr. Richard Wolff, just kind of edited together. We talked about covid-19, the end of capitalism, and the potential for building post-capitalist futures in part through democratizing our workplaces, so I think it was a fantastic series of talks. I hope you enjoy it. As I said on Patreon, we have some fantastic guests coming up that I am really excited about, so just another shameless plug for the Patreon. This is a donor-funded show. We rely on all of your generous donations to keep the show going. For just two dollars a month, you can get access to the Total Liberation Discord server that I co-host with Kathrin and Mad Blender, and we host bi-monthly political chats on there, so that’s twice per month and they’re always so much fun and really engaging, so definitely head over there if you want to be part of that community.

Otherwise to help the show, you can share the episodes with friends and family or give us those ratings and — no, you must; you must go and give us ratings and reviews on iTunes, Apple Podcasts, or whatever you listen to us on, only if you’re gonna give us five stars. But that really does help and I love reading the reviews, so thank you so much to everyone who’s done that. You could also just give us a one-time donation via PayPal on our website which is veganvanguardpodcast.com. With all of that out of the way, let us get into this interview with Dr. Richard Wolff.

[MUSIC] Richard D. Wolff is professor of Economics Emeritus at the University of Massachusetts, Amherst and a visiting professor in the graduate program in International Affairs of The New School University NYC. He’s the founder of Democracy at Work and host of their nationally syndicated show Economic Update. His latest book is The System is the Sickness: When Capitalism Fails to Save Us from Pandemics or Itself. It’s available with his other books Understanding Socialism and Understanding Marxism at www.democracyatwork.info. So, I highly encourage everyone to check out the Democracy At Work YouTube channel and also Richard Wolff’s personal YouTube channel because he does a really, really great job making all of this incredibly important and incredibly complex economic information accessible to a really wide audience. So, Richard, thank you so much for being here. We’re thrilled to have you on the show.

RICHARD: My pleasure Mexie, and thank you for inviting me.

MEXIE: Awesome. Okay, starting off; capitalism as you know, especially late-stage capitalism in this finance capitalist era is incredibly volatile and it’s prone to crisis. You’ve said many times that capitalism has actually crashed three times in the past twenty years, so I’m wondering — experts are fearing that we’re headed for a recession that will rival the Great Depression, so where do you think we are right now? How are current — how does our current moment compare to the Great Depression in terms of employment, housing, and food security, and where do you see things heading in the next five to ten years?

RICHARD: Okay, let me answer this way; this is the worst crash of American capitalism since the Great Depression. So, that means everybody watching, listening to this program, this is the worst economic crash in our lifetimes, all of us. It is a profound testimony to the fundamental instability of the capitalist system. If you look at the history of capitalism both in the United States and anywhere else in the world where it has settled, it has an economic downturn and by the way, many words for it; recession, depression, bust, crash. The language is full of it. Why? Because it happens on average every four to seven years. That is for centuries.

Everything has been tried in capitalism to get rid of this instability because the capitalists, the people who like capitalism always understood correctly that a system that crashes like this every four to seven years, throwing millions of people out of work, destroying businesses, interrupting or destroying educations, breaking up families, this disaster happening every four to seven years is hardly a recommendation for the system. So, they try, they really did try using their best minds to figure out a way to stop it, stop it from happening. To give you an example, the Great Depression of the 1930s, the president then, Franklin Roosevelt, went on the radio and gave a famous speech.

In the speech he said I have some plans for how to get us out of this depression and I want you to support me, and I promise you in exchange that these measures that I’m proposing will not only get us out of this depression but will prevent us from having more depressions so that our children will not suffer this kind of collapse of the economy the way we are. Roosevelt promised it and every president since has promised it, but no president has ever been able to deliver on the promise. The promise has been betrayed and we are now in the biggest betrayal since the Great Depression. The unemployment rates we have now are depression-era unemployment rates. The collapse of production, likewise.

But let me review the three that we’ve had in the — in our new century because in the way they illustrate the point. Early in the spring of 2000, we had a crash of our economy. We called it the Dot-Com Crash. Why? Because the prices of shares of dot-com companies had gone through the roof in the stock market. Now, you didn’t have to be a genius to understand that shares of — prices of shares go through the roof from time to time without causing a crash, so blaming it on the prices didn’t make too much sense, but it was very helpful to distract people from asking the obvious question; why is this system crashing again having been told that we had learned from the earlier crashes how to avoid it? Didn’t work; we had a crash. Seven years later in 2008, we had another crash.

The only difference was it had a different name. It was called the Subprime Mortgage Crash, again blaming the trigger rather than the system that’s unstable. It was worse than the one in 2000. Here we are in the year 2020; boom, we got the third one of this century and this one we’re gonna be calling the Covid-19 Crash or something like that, once again blaming the trigger that happens just at the same time rather than the system. Twenty years of a new century, three crashes works out to a little under seven years. Bingo; just what we would expect. Most people knew that this crash was coming and predicted it long before we knew anything about the virus and what it would do. So, for me, I see this as the worst crash of the three. That’s not a good sign.

It shows us that the measures taken after 2000 didn’t prevent or reduce the awfulness of the one in 2008, and now again only moreso since 2008 to this one. We have the pandemic which no doubt makes it much worse. This is a system that seems to me to — and let me stop with that — to have failed. There’s no nice way to say this. You know, viruses have been with us from day one. It’s part of nature. Viruses are things in nature that can be very toxic to plants, to animals, to people. We had a terrible one a hundred years ago in 1918, very famous. People know about it. We’ve had more recent ones; MERS, SARS, Ebola. We know and we should have been prepared. What in the world is wrong with a system that didn’t prepare for what we knew was coming?

Sort of the same question that the fires in the west coast are making us — we knew what was happening and here we are with our fingers in our noses because we don’t — we haven’t gotten ready and now we’re not containing it. The United States is a rich, capitalist country. We have 4.5% of the population of the world and over 20% of the covid cases and the covid deaths. That failure of a system — last point; why do I keep saying it’s a failure of the system? Here’s the way to make it really clear; I understand that no capitalist company of the kind that might produce tests or masks or ventilators or hospital beds, they’re not gonna produce those beds, store them in a warehouse somewhere, make sure they stay in good shape for an indefinite amount of time before they can sell it.

They’re not gonna do that because it isn’t profitable. Capitalism says to the company you do what’s profitable and you avoid what isn’t. So, they don’t produce those things. Okay, we all understand that. The government then can compensate for the failure of private capitalism to manage this situation. By the way, this situation is called public health, a fundamental need of human beings. So, private capitalism stinks at taking care of public health for the reasons we all understand. Well, the government could come in. You know, the government could buy up tests, masks, ventilators, ICU units, all the rest of it, and store them around the country and make sure they stay in good shape, replace them if they wear out, blah, blah, blah.

We know the government can do it because that’s what it does with military equipment. It doesn’t pay a company to produce a tank or a machine gun or an airplane ‘til the government comes in, buys all that stuff, making a nice profit for the companies that produced them and then the government, at its own expense, that is you and me, pay for storing it and locating it around the country for a military emergency. But our own government didn’t do that for a medical emergency, so we were unprepared and we are now paying the price; 200,000, nearly, dead. It’s unspeakable what’s going on. The failure is catastrophic. I don’t think I have to explain to people that we can do better than capitalism. We’re living through the proof of it.

MEXIE: Yes, absolutely. That was incredibly well-said. You mentioned what the government could have done that they’re not doing; at the beginning of this crisis, I actually thought that this could really, really shake up — this could be the end of capitalism as we know it because I wrongfully assumed that the ruling class, the politicians, they would be forced to make some concessions, they would be forced to provide debt relief, rent relief, maybe even basic income if only to avoid the inevitable unrest and the possible radicalization of the masses. However, they’ve only provided $1,200 so far and now millions of Americans stand to become homeless. Why do you think the bourgeoisie is taking such an incredible risk and do you really think they’re going to just let this happen?

RICHARD: That’s a wonderful question. I put it almost this way; in the history of the collapse of empires, the Greek Empire, the Roman Empire, the British Empire, when the historians go back, they look at the years and sometimes we’re talking decades before the thing collapses. They say to themselves as they look at the history, how could these people not have seen what was coming down the pike at them? Why in the world didn’t they do this or that which seems, with our 20/20 hindsight, to be the obvious thing you should have done? We have it even worse now because what the United States did is much worse in terms of the risk the bourgeoisie is taking than they did in Germany. Let me give — or Europe. Let me give you an example; before the pandemic hits Germany, unemployment was 5%.

Over the summer, unemployment in Germany rose to 6%. In other words, very little. We went from 4.5% to 20%. It’s a spectacular difference. Why? Because in Germany it was understood that had the government thrown millions of people out of work, allowed that to happen, those millions of people would have left their job and gone right into the street, and Germany would have come to a halt. They know that and it’s true in France and Italy and you fill in the blank. They couldn’t. Here in the United States, it’s a different situation. They can and they think they can go quite a bit further, and they think that because for the last twenty-five years, they’ve been going further bit by bit, leading people like you and me to ask exactly your question; how in the world do they dare do that?

The answer is, they were worried but they saw there was no apparent cost. Now, it’s a — it’s still a risk. You’re still right to wonder because yeah, nothing may be happening but under the surface, who knows? Let me be very concrete; we have a labor movement, the AFL-CIO, right? It is the dominating labor movement of this country. We have the worst unemployment since the Great Depression. Has the labor movement called for a demonstration? No. Has it brought people into the streets? No. Has it raised hell in twenty-seven different ways? No. So, the people who say we gave the unemployed an extra $600; the Republicans are now proposing to reduce it to $300. Why should they give $600? Make the mass of people desperate. It seems that you can kick them and they don’t kick back.

Therefore, if — and they’re scared, by the way. Let me — I don’t want to leave the wrong impression. The people running this society know how bad it is and they’re very worried. They’re borrowing money. We have a three trillion dollar debt this year in the budget. We’ve never had that before except in World War II and even then, not this big. They’re very worried that as these debts accumulate, the American people are going to have political leaders who are going to say gee, if the debt is so high and that’s costing us so much, let’s reduce the debt and here’s a way to do it; we can tax corporations and the rich, pay back the people that the government borrowed from, and then we’ll all be better off and the rich will still be rich, they just won’t be obscenely — the obscenely rich understand this very well.

They want to keep this from getting to that point. So, it’s interesting for them to reduce what we give to unemployed people from 600 to 300. That way they slow and postpone the day when all of this comes due. So, that’s why they do it and they think they can get away with it. By the way, all those empires fell because they kept doing it and then they did it the last time when it turns out you couldn’t get away with it. My suspicion is we may be very well down that path, that yes, the United States doesn’t push back, the Americans don’t, but when they finally do, watch out.

MEXIE: Right. Yeah, I feel like they’re just counting on our ignorance of the situation, basically, and our ignorance of political economy in general and just seeing how far they can go, because they can’t…if they did those things, if they did give debt relief and all of those things, it would be kind of admitting that their whole — the whole ethos of American and Americana is wrong, right?

RICHARD: Absolutely. Here’s a wonderful way to capture that; if you look around, you will notice that in recent months conservative people, right-wing people, the people who used to attack welfare moms, you know, single mothers with children who had to take care of the kids and couldn’t go to work and therefore went on the dole or went on welfare and got welfare payments were being attacked as lazy or criminal or all the rest of it. You don’t hear that. You don’t hear it and the reason you don’t hear it, I’m convinced, is because welfare is how everybody now lives. Let me give you just two examples. One-third of all mortgages in the United States are now owned by the Federal Reserve System of this country. Here’s how it works; Mr. and Mrs. Smith go to the bank to borrow money to buy a house.

Mr. and Mrs. Smith borrow the money and they write an IOU. It’s called a mortgage. They owe the bank x dollars and they pay it off so much every month. Here’s what happens; the bank immediately — I mean within minutes of the papers being signed — the local bank sells that mortgage to the Federal Reserve which gives them cash so they can do it all again with Browns and Greens and everybody else in the community. The ultimate creditor, the one who provides the money to keep the housing market going is the government. The housing market is on welfare. The Federal Reserve simply prints the money and hands it out to the banks currently at almost no interest rate, so the bank is happy, gets this cheap money, turns around and lends it to people who want to buy a house at 3%, 4%, 5%; they’ve borrowed it at half of 1%.

Money for the bank, lots of houses can be financed. But they’re all on welfare. It’s government money makes it possible. It’s this type of example. The Federal Reserve is now buying what are called corporate bonds. Here’s how that works; a company has a problem. It can’t pay its workers, it can’t sell its output, it has an outmoded technology. Whatever the problem is, here’s now the easiest way to solve it. You go to the Federal Reserve, you write out a bond; I want to borrow money at an interest rate of half of 1%. That’s the easiest, cheapest way to solve whatever problem your company has which is why American corporations today are deeper in debt than they have ever been in the history of the country. Who’s holding that debt? Who’s the creditor? The Federal Reserve. In other words, corporations are all on welfare.

They’re getting a cheap — just like if you’re on Section 8 in this country and you get help with your rent, you’re a family in difficulty, you get help. You’re a corporation in difficulty, you get help from the Federal Reserve. You can’t make fun of the welfare mom anymore because she’s the least of the recipients of welfare. It’s all the rich corporations and so forth who are living off of the government. It’s the failure of private capitalism, you bet.

MEXIE: Yeah, yeah.

RICHARD: But the conservatives will continue to celebrate the private enterprise that isn’t there anymore because they’re hold — but that’s the sign of a collapsing empire. It has to make things up that are so completely disconnected from the real world that it really is becoming a matter of time until that disconnect catches up with them.

MEXIE: Yeah. Absolutely, yeah. They may think that they can keep going for now but I think that a lot of people are being radicalized by this moment. We’re already seeing a number of wildcat strikes being organized on the ground, a lot more people are joining labor unions or unionizing their workplaces, and then of course there’s this whole global uprising to defund and abolish the police who are the protectors of private property and capitalism itself. So, what are your thoughts on all of these developments and what do you think the people should be doing to organize themselves right now to force a change?

RICHARD: Well for me, these are all straws in the wind. I celebrate them, these are things I have hoped for I’ve felt were missing. I am pleased, I am satisfied, I am — I’m inspired. By the way, it all affects me, too. I get invited to places I was never invited to before to speak. I have audiences I didn’t know existed and their level of enthusiasm is — it’s infectious. It keeps people like me going. We wouldn’t be able to keep going or talk the way we do if it weren’t for the feedback that we’re basically getting from people who have figured most of this out in terms of their own lives and their own experiences. I do think there are two things I would point to that are, for me, the biggest stumbling blocks or the biggest tasks we face.

One of them, and not necessarily the most important, but one of them is best captured by the word ‘organization’. Americans have been bitterly disappointed in organizations, all kinds. You know, we pride ourselves on being isolated, loners, we celebrate the loner, the independent, the self-reliant, all of that. Some of that is good stuff but others of it is kinda fantastical and make-believe. We do depend upon one another whether we can face it or not. But the sad thing is that the left — which is very numerous in this country and runs very — it’s very deep. It’s a wonderful community but it fails to get itself together. It fails to organize. If you get interested in an issue, you have until recently been very focused; you want to work on that issue and you don’t want people who are focused on something else that’s more important in their lives.

Then you have these sterile debates; who’s got the most important issue? Are we oppressed mostly because we have our gender or our sexuality or our skin color or our education? Stop. This is a system that breaks people apart because it’s terrified of the possibility of what might happen if a organization of the majority — and I’m an economist so let me tell you what I think the root of that is. We have an economics system in which in every enterprise; factory, office, store, what do we have? A tiny group of people, the so-called owner of the enterprise or the board of directors of the corporation or the major shareholders. Whatever you want, this is a tiny group of people, a small minority of all of those who work in that enterprise, in that factory, office, or store. That small group of people make all the key decisions.

They decide what gets produced, they decide what technology is used, they decide where the production happens, and they decide what happens with the output. Do you sell it? Who do you sell it to? At what price? What do you do with any profit? All of those decisions are made by a minority and they are told to the majority who has to live with it and shut up because if you say something, they can also fire you and then you lose your job and lose your income and lose your chance to advance in your life, et cetera, et cetera, et cetera. This is a horrible, undemocratic system and I think it leads to a kind of passivity. It leads to a feeling I can’t control anything. Because where you work, that’s where you go five out of seven days of the week. That’s where you spend most of the waking hours of each of those five days.

To imagine that that’s not gonna shape you in a basic way is naive. Of course it will. It’s difficult then to get yourself motivated to be an activist out of the workplace when the workplace is so structured to make you passive, to resign you, to make you accept. Because what can you do? The notion I can’t change the world starts in the workplace if not earlier in your family which often — so, I think overcoming this situation, being aware of it so that you can fight it. If the American left, even the size it is now, if it were organized, the impact on our society, its power would be fifty times what it is now. Bernie Sanders would have been the candidate, not Joe Biden, and so on and so on and so on. That’s the first.

The second one is — and I know being an academic, this may be hard to swallow and maybe that’s why I believe it — it does make sense to study and learn and to have a strategy and to have a theory about what’s going on, otherwise you’re helter-skelter every which way. Not that you have to believe the theory answers all the questions. No theory does and if a theory pretends, don’t pay attention to it. But a theory is a guide, a rough guide to what to do. For me, the biggest thing right now is to understand that capitalism, the system is the problem, that we’re not gonna fix it or improve it or perfect it or get rid of this or that impediment. We’ve been there. We’ve tried all of that. It doesn’t work.

That’s why we’re in the disaster we’re in and it’s time to face — and this is the theoretical point — that the system is the problem and that system change is the solution, and that that change has to happen in our personal relationships, in our workplaces, in our residences, all over the place. That’s what system change means. I know it’s scary but not to change the system is proving to be scarier.

MEXIE: Mm-hm. Yeah, no, absolutely. So, I wanted to ask you about I guess the end of capitalism, right? So, I feel like even before covid-19 hit, the contradictions of capitalism have never been so pronounced, right, between decades of outsourcing and automation and the global environmental crisis. It seems like we just don’t have anywhere else to go. However, capitalism just has always been so resilient and able to turn what would be externalities into new avenues for profit, et cetera. So, do you see ways that capitalism can hold on despite these worsening contradictions and do you see it living out the century?

RICHARD: Great questions. If we had fifty hours more, we could work our way through. Look, I understand — there’s a joke that used to be made about Marxist economists. The joke went like this; Marxist economists have predicted ten of the last four recessions. The answer being Marxists keep seeing the end of capitalism and it doesn’t show up. Look, I’m not a predictor. I don’t believe in prediction. I can’t tell you when this system will disappear, but I don’t feel I have to prove that it will and here’s the reason; every system before capitalism displays the following pattern. It’s born, it evolves over time, and then it dies and passes away. We had slavery; it was born, it developed, it died. We had feudalism; born, developed, died. We have capitalism; born, developed, what’s the next step?

For me, it’s not a question of whether. It’s a question of when and how. I’m — for the first time, because I hadn’t felt this way before — I am now looking at a system — I don’t see how it gets out of the dead end it has waltzed itself into. In this country in particular, Western Europe, North America, Japan, I think capitalism is exhausted here. Not in Brazil, not in India, not in China. They still have a ways to go because they were late to the party, but we were the early ones and we, the capitalists, initial parts of the world, we can’t solve our problems anymore. That’s what’s showing up. We can’t keep ourselves healthy, we can’t prevent our forests from burning down, we cannot solve our racial — we cannot solve our misogynistic history, we can’t deal with the problems that we have and that’s a sign of a system that’s exhausted.

I see the signs around me and so, I’m beginning now to think in an ongoing way that we are in a declining system which is difficult to face up to. It’s hard to go through. The last century have seen the British people still unable to understand that their empire is over, acting as if they were something other than a small, cold, wet island off of the mainland of Europe. I mean, and that’s hard. I understand that. We’re gonna have the same difficulty and I see Trump and the horrors of what he represents as a symptom of a declining system raging against the world. This morning, the World Trade Organization reached a conclusion that the tariffs Mr. Trump imposed on China are illegal, contrary to World Trade Organizations, and have to stop. Look at that; there he was, Mr. Rageful, punishing the world with tariffs. All it did was unify the rest of the world against the United States.

These are the ragings of a person who can’t effectively accept that the game is coming to an end and we have to adjust to play a role in the world that is something other than king of the hill that we believed before. That I think is the real challenge of how to manage this decline so it doesn’t take us all down with it.

MEXIE: Mm-hm. You’re a big advocate of building worker cooperatives and of democratizing workplaces from the bottom up, so could you give us an idea of how democratized workplaces and decentralized production could have helped us cope better with covid and perhaps could have helped us mitigate some of the economic recession that we’re now dealing with?

RICHARD: Sure. Let me start with the easiest example to give that goes something like this; in a capitalist system, a very small number of people, group of people, make all the key enterprise decisions. We call them employers. There’s no mystery about it at all, and if you put all the employers together in a big stadium, it wouldn’t be more than 2% or 3% of the American population, to take our country as an example. It would be the same percentage in other countries. The vast majority of people are employees, not employers. So, you are doing something remarkable when you put the economy on which we all depend into the effective hands of a tiny minority and give them all the power. The employer decides what the enterprise is gonna produce and this is true whether it’s a factory, an office, a store.

Doesn’t make any difference. A tiny number of people, the employer, the board of directors if it’s a corporation, the owner of the business if there is one, et cetera, et cetera, the major shareholders; you put them all together, as I say, 2% to 3% of the population. They make all the decisions; what the enterprise is gonna produce, what kind of technology the enterprise is going to use, where the production is gonna take place, and then the really big one, what to do with the output that everybody, all the employees and the employer, whatever they’ve done, whatever we’ve produced, this tiny group of people decides. For example, we’re gonna sell it in the market. Okay, and then they get the revenue from that. Okay, and then they decide what to do with it. What happens to all the other — the employees, the vast majority?

They are told a very interesting thing at the end of each day. Go home, get outta here. Go back home, have a beer, maybe some pizza, and then come back tomorrow and do it all again. Oh, and by the way, what you helped to produce today using your brains and your muscles, that’s ours. That stays here. You go home but the product belongs instantaneously to us, the employer. Even if we didn’t do anything to lift a finger to produce it, it’s ours. It’s the way the system works and we will do with it what we want. The decisions of those 3%, the employers, we the employees have to live with them whether we like them or not, and we have no input. We don’t have a veto power, we do not elect these people. We have absolutely nothing to say.

We are required to live with decisions we cannot participate in. That’s the opposite of democracy, so if you are committed to democracy, whatever you think is the way to express it, you are — when you go to work in a capitalist system, you are saying goodbye to democracy. When you cross the threshold into that office, into that store, into that factory, you are entering a place where a tiny minority of unaccountable people at the top tell you where to go, what to do, what desk to sit behind, what machine to use in what way on what raw material, and at 5:00, get outta here. I like to make the joke that there’s a reason why the bar that you pass on the way home from your job has in the window Happy Hour, because it knows like you do that those other hours where you are a drone being told what to do, those are unhappy hours whether you admit it to yourself or not.

Okay, for me, this is the root of the problem. To take the example of the pandemic, mask producers in America — and we have them; we have factories that can produce masks. Okay, those people knew that masks are used when you have a pandemic, a viral pandemic. This is not the first one like this. We’ve had these all over the place and we can see on TV over the years people running around with masks. No rocket science here. They could have produced those masks but they didn’t. The answer is it wasn’t profitable, and they’re right. It wasn’t. It’s very easy to understand; when we teach economics which I’ve done most of my adult life, we are instructed to teach that capitalism is a system that is based on efficiency, that what capitalists do is figure out the most efficient way to produce things and isn’t that wonderful?

We don’t waste anything. Alright, here’s an example of capitalist efficiency if you want one. Any estimate one could make of what it would have cost the United States to produce all the conceivable masks we could want and store them, and ventilators, and gloves, and hospital beds and all of it is a tiny fraction of the amount of wealth we have already lost and we’re not even through this. This is the most inefficient catastrophe imaginable. All the little efficiencies accumulated by companies that can scrimp and save a little over here and make sure the light is turned out at the end of the day when the workers go home. All those little efficiencies are completely negated, overwhelmed by a monstrous inefficiency of the sort and I’m not even getting into what the value is of 210,000 dead fellow citizens.

Just the monetary loss, output not produced, I mean, it is awful. So, it stands as a critique — this is no way to function. This is a system that is busted, broken, ineffective, screaming its incapacity and its failures to a world that even the amount of endless propaganda about efficiency and capitalism and — it can’t drown out the noise of its failure. It’s beginning to overwhelm the BS that it pays for.

MEXIE: Absolutely. Even the pope just came out and said that capitalism…

RICHARD: Yes, basically — by the way, for those who haven’t seen it, it’s relatively short and cyclical; Fratelli Tutti, I believe is the name that Pope Francis issued, is as strong a critique of capitalism as you’re gonna see, and way better than most of the politicians who even dare go in that direction are able to say, so it’s remarkable.

MEXIE: Yeah. So, Amanda’s question is about your — does your new book address our need to transition away from capitalism and what’s our next step? That kind of ties into the next question that I wanted to ask which is basically that within this broader capitalist system, existing cooperatives are forced to compete with one another and with other businesses to some extent, so I’m wondering how existing cooperatives could potentially coordinate resources or cooperate and do you see this as a path forward towards some kind of post-capitalist economy be that socialist, anarchist, communist, whatever?

RICHARD: Yes. My new book does address that, and so let me also comment on it here. Yes, I am now convinced — and I wasn’t until relatively recently — that we are living through the decline of capitalism. I know that capitalism has been very resilient for two, three, four hundred years, and that’s an impressive record, so I know I could be wrong. I’m not dogmatic about it but for the first time in my life, and you can all take it for what it’s worth, I think it’s over. I don’t know exactly how that plays out or what it means for our lives but I think with experiencing now an accumulation of unresolved problems that are typical of a society that has kicked the can down the road as many times as you could, and it’s now catching up to you. We have a health crisis that we can’t handle.

We have an economic crisis that is the worst in this new century, second only to the worst of capitalism’s entire history, the 1930s, and we may yet beat that record. Our racial difficulties are coming to a explosive head. We are still in the stage of a women’s revolt that comes out of the whole sexual abuse catastrophes that we have pretended weren’t there for all this time. Look at it; I could go on. We have the climate crisis, we have fires burning in the west that are terrifying, and we had an earlier batch of them in Australia. It’s just, whoa. We can’t — these are difficult problems each by itself but the collection, the coming together, that’s why we’ve had several years in which one of the most impressive tropes in our arts have been movies about tsunamis and monsters and earthquake — this is the artistic intuition, which is always profound, that it’s falling apart.

I’m afraid I have to add as a professional economist, it looks like that to me, too. It’s falling apart, which means we do have to ask Amanda’s question where do we go? What do we do? That’s why I focus on worker co-ops. That’s a new place. That’s another way to organize our society. You know, for a long time, societies were organized around two positions; master, slave. A tiny group of people were the master, most of the people were the slaves, the masters made all the decision, they told the slaves what to do; you all know. Then we got rid of that and we replaced it with something different, we thought; lord and serf, feudalism. It was different. The serf wasn’t anybody’s property, no mind or matter. No human being is the property of another human being.

But there was some similarities, too; a tiny group of people called lords, maybe 3% of the population making all the key decisions for the mass of people who are serfs. Then that system was overthrown by people who wouldn’t tolerate it anymore and we had capitalism, and it is very different. There’s nobody who’s a slave and there’s nobody who’s a serf tied to the land and none of that. It’s a deal we make; I work for you, you pay me a wage. Yet, it too had a similarity; 3% of the people made all the decisions in the workplace. The employer took the position of the master and the lord, and the employee took the position of the serf and the slave. So for me, the solution is stop it. Bring democracy to the workplace. Make it something that is owned and operated by the workers themselves. One worker, one vote.

You decide collectively, democratically what you’re gonna produce, what technology you’re gonna use, where you’re gonna do it, and what you’re gonna do with what you all helped to produce. We are talking in a country, an area of the world; let’s call it North America, where you’re supposed to take the concept of democracy really seriously. Well, if you did — and I want to be provocative here — if you did, you’d have to ask yourself the question why have we excluded democracy from the workplace for the entire history of our societies? By the way, in the way that Native Americans didn’t. The Iroquois were the only ones that I know a little bit about had a very democratic way of deciding the hunting and the gathering and the agriculture and so on. They didn’t have a tiny group who told everybody what to do.

We do that. That’s capitalism. I think we got rid of kings a few centuries ago because we didn’t all want to be subjects with some king who could be for all we knew the mentally challenged child of the previous king, that this was nuts what we were doing, and that we would prefer to have a situation where everybody got a vote and we elected people to a congress or a parliament that would make these decisions and not be left to the whims of an individual or have to be born to somebody. We got rid of the kings. But here’s the joke and it’s not a good joke; the kings are still with us but they’re inside the workplace and they changed their names. They’re now the boss or the CEO and they still have that kind of power inside the workplace that we wouldn’t allow outside. What is that?

Why — where’s that come from? I think, to say it in a sloganizing way, but it captures it. If you want an economy to work for all the people, you’ve got to put the people in charge. You cannot put a tiny minority in charge and then be surprised that they arrange things that are good for them. Capitalism is wonderful for the top 5%. They are rich, they are secure, their wealth is growing relative to everybody else’s. They live in palaces, they are surrounded by the gated community. You know it all. We all know it. That system’s good for them but not for us and it’s about time we kind of face it, and the way to deal with it at the base, foundationally, is to say change the enterprises. Make all enterprises a collective effort of the people in it, in corespective relationships to the communities in which they live, democratic residential governance, democratic enterprise governance; work these two together, that’s a new and different way of organizing society. That’s the way we have to go.

MEXIE: Yeah, that’s really, really well-said. At first I thought well, it would kind of have to be at both levels, right? So, you’d have democratizing the workplaces from the bottom up and then also organizing to take control of the government because as you said at the starting, if we’re going to do things that are good for the general public good, then we kind of need the government to step in in some way if those things are still really expensive. But then yeah, hearing you talk more about this, I thought that part of the reason why the government works so much for the market or the CEOs or whatever is because they’ve been able to amass an ungodly amount of wealth from the system of being the kings of the workplaces. So, with that wealth, they have an undue influence over our democracy at the state level, so if nobody was really amassing that level of wealth individually, then maybe things would look differently at the state level as well. I don’t know about your thoughts on that. Also, Joe said that in his estimation there are two possible outcomes; arise in progressivism or violent revolution.

RICHARD: Yeah, I think Joe has a point. I’ll come back to it. Let me deal with yours. It’s a very old and basic problem; if you are a large society and if you allow wealth to concentrate in a very small part or portion of your society — this is true whether it’s a village or a city or a country or the world — you immediately have an enormous tension. First of all, the rich, they understand what we’re talking about very well. They understand that they have an enormous amount of wealth relative to the average person and that the average person outnumber them. If you have a political system that is committed to universal suffrage in which everybody or every adult has the right to vote, then you are immediately in danger if you’re a very rich person that the majority aren’t, and that the majority will control the government by voting and that they will undo the results of the economy.

They will change it; they don’t like it. They don’t want you to be terribly wealthy and they can’t feed their family or get their kid through college or any of the other basics that they think of as basics, if they do. The rich people have understood that their wealth is jeopardized. It’s vulnerable, deeply so, so they better do something. They can’t undo universal suffrage although if you know the history, those people fought it every step of the way, but you can’t undo that. That won’t work anymore. Okay, so what do you do? Number one; you take a big chunk of your wealth — don’t be stingy now — and you give it to the political parties that you want to be in office. You give it to all of them. If there are five, dish it out to five. Europeans do it all the time. If there are two as in our country, dish it out both of them.

Make your American corporations work to both parties. Why? Then because all these parties are not gonna take the steps to undo your wealth because you’ve made them dependent on you. Here’s another thing; flood the economy. Spend a lot of money full of academic studies by professors with good reputations from the best universities explaining that whatever the government is doing for these rich people is really the best thing for all of us. It’s childish what’s going on but that’s the game, and they’ve been quite good at it which is why we are in the mess that we are in. They have to do that, otherwise we’re gonna vote in — well, let me give you an example; we will vote in Bernie Sanders.

Bernie Sanders is committed to a much more progressive tax structure than what we have, and that’s a polite way of saying he’s gonna move wealth from the rich to the middle and the bottom which reverses what the last forty years in America have been which has been a redistribution of wealth the other way. They know that. They know that real well and that’s why they support Mitch McConnell and the Republicans and Trump and prefer Biden to Bernie Sanders. No rocket science difficulty here. Let me if I can, Mexie, respond to another thing you said. I know we’re running out of time but it’s so important. One of the things that has to happen when capitalism goes, which I believe it is in the process of doing, is that we’re gonna understand that our ways of thinking were shaped in profound ways by that capitalism and that we have to kinda adjust.

It’s a little bit like a farm person coming into the city or vice versa. You have to — different rhythms, different ways of looking at the world, different ways people connect to each other. Those have to happen and here’s why; competition. Okay, there’s always been — ancient Rome had competition and Greece had — they didn’t have capitalism. Competition is one thing. Capitalist competition is another. So, in capitalist competition, if my enterprise produces a better widget than yours and can do it at a lower price, everyone’s gonna buy my better widget at a lower price and you’re gonna be destroyed as a business. You’re gonna go bankrupt, you’re gonna feel terrible, you’re gonna have to fire your workers. Ugh, death. It’s very dangerous, very scary. But it doesn’t have to be that way.

I’m gonna give you an example. Inside a large American corporation there are divisions. Suppose one division doesn’t do well. Do they simply say okay, you’re gone, you’re fired, you’re…? No, no. They don’t do that at all. They figure out okay, let’s reallocate. We don’t need 400 people in that division. It’s not doing that well. Let’s see, maybe it’ll do better but for the time being, we’ll take fifty of those people and move them over there because there we have something that’s growing and that needs more people. They will, and nobody has to worry that if your division has a difficulty, you’re dead, you’re gone, you’re finished. Well, you know, a worker co-op society would do exactly the same thing. Let’s suppose we have a worker co-op and for whatever reason they’re inefficient, maybe people don’t like what they produce anymore.

Whatever the difficulties, they can’t sell whatever it is that they make in the quantity they used to; only half. In some way then, in some rough sense, half their workers are in a sense not needed there. Well, in a capitalist system, the employer immediately says you’re fired. I’m not gonna pay you wages if I can’t sell what you helped to — but a worker cooperative, that’s crazy. Having a person who continues to eat, to wear clothes, to use shelter; he is consuming but he’s not producing. That’s irrational. He wants to produce; he’s a healthy worker. Our job is to find him another — so, we will arrange okay, if this area is shrinking in its demand for labor, here are areas in our community that could use some more workers. Maybe to help old people, maybe to reclaim an ecologically damaged region, maybe to do a green new deal. Who knows?

But there’s always plenty of things to be done and the system would guarantee the enterprise is not gonna fold. It’s gonna be smaller. Another enterprise is gonna be bigger and when the wind changes, it’ll go the other way. But we’re not gonna allow the competition and we’ll keep the — they should compete. That way we get improvement over time. We want that. We want innovation and all that, so we will have competition but we will not allow it to work this way as it did in capitalism. That has to be understood, otherwise you’re gonna think oh my god, how different is it really gonna be? The worker co-op is gonna be as tight-fisted and hostile to its own members as any capitalist employer was, and the whole premise of this system is no, we’re not gonna do that. We’re not gonna treat human beings that way.

That’s why we’re not capitalists, ‘cause we don’t want that kind of — we want our worker to understand it is the obligation of society not only to give you a safe way to be born into this world and a safe, dignified retirement out of it, but we are also going to give you a decent job with a decent income as something you can rely on. Now, go out there and develop your mind, your spirit, your hopes, your dreams. Go out there and make a better world, but you don’t have to worry about whether or not there’s food on your table, that there’s a job for you to go to. We’re just not gonna do that to you because it’s socially irrational and personally destructive. The only way you can justify it is if you have a system based on private profit.

If you want to give a small group of people the position in society where they can fire you if and when it is more profitable to them, which is what we have, if that’s what you believe in and if that’s more important to you than giving the mass of people what we are capable of giving them, then you are really a pro-capitalist person. But I think that’s as tiny a minority as are capitalists themselves. If the majority were given half a chance to pursue what I’m saying, we would do it. Italy is a wonderful example. There’s a province in Italy, in the north of Italy around Bologna called Emilia-Romagna. It’s a part of Italy. In that economy, for decades now, about 40% of all work is done in worker co-ops. It is the most developed regional worker co-op system in the world.

They fought for it and they’ve kept it there because the mass of people want it. There, you can see how they work, what the interactions are between capitalist enterprises and worker co-op enterprises, how the politics is shaped, but the notion that we can’t do it or that it isn’t possible, that’s all wrong. That’s only based on keeping Americans — I’m talking here loosely, but keeping a lot of people, not just Americans, unaware of the fact that worker co-ops are a very old idea, not new, been around for thousands of years, are much more in the world today than you know about because we haven’t yet — that’s what I’m working on — become aware that we should be paying a lot of attention to them because they contain the seeds of a new world. Like with anything else, there’s no guarantee those seeds will germinate and grow and all the rest. But I think it’s now a possibility and the collapse of capitalism — I’m hanging onto this metaphor — the collapse of capitalism provides the fertilizer for this.

MEXIE: Yeah. No, absolute — that’s so interesting. I actually hadn’t heard of Bologna and their worker co-op setup, so I’ll definitely look into that. As a chronically-ill person, yeah, moving towards that kind of a system sounds wonderful to me and I agree with you that I think that capitalism is absolutely circling the drain and if we can both attack it kinda from the top down but also build something up, like the sharing economy that can take its place, I think that’s definitely what we should be working towards right now.

RICHARD: I think so too because as I look at the collapses of previous history, systems change not because a new idea comes along and not even because a new idea catches hold and inspires people. It mostly comes to an end because a system can’t solve its own problems anymore. I think that’s where we are. We are just unable. The United States has gone from the leader to a country about whom we can say we are 4.5% of the people of the world and we’re 25% of the world’s covid cases and 25% of the covid deaths. We’re a rich country with a developed medical system. That is such a failure on such a scale you’re gonna never live that down. This is going to be for the United States as the leader of capitalism what the Bubonic Plague was for feudalism in Europe; the beginning of the end.

But I think that what happens is when a society implodes, breaks down, it’s at that moment the key question is who has some idea of where else to go? It’s sort of what do we do now? We’ve had it with this system. We will not take it another day. The revolution’s over. But that leaves the huge question and at that point it doesn’t matter whether it’s all that many people. If there are at least a few people who say well, here’s a direction that gives us a good reason to believe if we try that, we will get a better out — that’s what worker co-ops are. That’s why it’s important that they’re around, that we’re talking about them, that we’re thinking about them, because when that collapse comes — which is really the timetable of capitalism — when that time comes when everybody wants to see the alternative, the question will be how much have we spent thinking about, how much time? How well-developed are some of our ideas? How many times have we gone over them, challenged each other around them? That will determine how effective we are at that moment in giving the end of capitalism a new direction.

MEXIE: Mm-hm. I think it’s really important too to actually practice that stuff, right? If we actually want a world where workers own the means of production and we have a democratized government, you actually have to practice what does it mean for me as a worker to engage with other workers on equal footing? ‘Cause you don’t just — we’ve been completely socialized in the opposite direction so you don’t just one day wake up and know how to do that. It takes a lot of communication and problem solving and a lot of things that we don’t know how to do.

RICHARD: Exactly, and that’s why Emilia-Romagna is so interesting because if 40% of your regional economy is worker co-ops, it means that a typical Italian family having a picnic on a Sunday afternoon in a neighborhood park, gathering together the cousins and the aunts and the uncles and all the rest, they’re gonna have people in that picnic from both the capitalist sector, people working in a regular — and somebody working in a worker co-op, and they’re gonna talk about the — they’re gonna have their gripes and their things they’re happy about but you’re gonna learn about it. One of the reasons I’m so confident in the worker co-op is the people of Emilia-Romagna have built, have grown their worker co-op sector. When everybody knows about it, it doesn’t disappear. People want it.

It’s the capitalist sector that’s more worried about its long-term viability. The worker co-op sector has a sense that it is emerging. You have that in Spain too, around the Mondragon Corporation which is the Spanish version of this. They too are very good; big and strong and growing. I mean, they have their problems, don’t forget. We’re not talking about nirvana here. We’re talking about a change that will bring its own problems. It’s like the old story that my grandmother told me, that she warned me when I was thinking of getting married not to think that marriage will solve all my problems, which frankly hadn’t occurred to me. She wanted me to understand that when you get married, you exchange one set of problems that go with being single for another set of problems that go with being married. You have every right to prefer one set of problems to the other so you make the change, but it’s not going from problem to heaven. If you have that mentality you’re gonna be in for a rough ride, certainly.

MEXIE: Yeah, absolutely. So, I’m conscious of your time. We’ve gone over time, here. Do you have to head out now or…?

RICHARD: No, let’s go another few minutes.

MEXIE: Okay, so Joe said but how do we pay for it? Is anyone else sick and tired of hearing that? This reminded me of — we got some other questions in the last stream about how you feel about modern monetary theory and the importance of government debt.

RICHARD: Yeah, well, whether you take — modern monetary theory is a way of restating old ideas and also dropping a few of them that were hard to hold onto. The basic idea is that the government issues money and it can issue it whenever it wants to to get things going that it wants to get going. If and when this activity leads to being inflationary, that is, there’s too much money running after the goods and prices start going nutty, you pull the money out and that undercuts the ability of people to afford paying those high prices. I think it’s corrective, it’s valuable over what existed before, but it is like always prone to a bit of excessive enthusiasm; well, we can then fund everything. No, you can’t. You have to be careful. If an inflation comes, when you pull the money out, it doesn’t impact everybody the same.

That’s a very politically-loaded process which is why it’s so hard for societies to pull back. It’s so much easier to pump in. So, but all that aside. When the — we’ve had three crashes and here’s the way that I would answer it. Three crashes in the 21st century; the so-called Dot-Com Crash of the market in spring of 2000, the Subprime Mortgage crash in 2008, and now the covid-19 crisis in 2020. Three crises in the first twenty years, each one worse, much worse than the one before. In these situations, in each of them, the government suddenly panicked as millions of people lost their job and tens of thousands of businesses went belly-up, and no one batted an eye. It took a matter of days to spend unspeakable amounts of money, billions and then trillions of dollars to keep this capitalism from blowing itself up.

Anyone who looks at the amounts of money involved and then responds to the notion — what about something as fundamental as giving the economy diversity so it isn’t all the capitalist type of top-down hierarchical enterprise, but we also have a worker co-op sector, a place where we take democracy seriously inside the workplace, and we have the two so people can see what it’s like to work in one or the other or what it’s like to shop from one or the other, and we begin to have an informed population that can then decide democratically what kinds of systems it wants? Right? That should presumably be a very important thing fundamentally changing the country, and of course, the small fraction of what they’re spending to keep this broken system from complete collapse.

Let me make sure your audience understands something which has so far escaped attention. During this covid crisis, the Federal Reserve — which prints the money, basically; either physically ordering the bills and coins or electronically creating the accounts — they have begun lending directly to corporations. Here’s what that means; any corporation in America, any business that has as problem; the public doesn’t like what they produce, they’re not buying it, or they have a fight with their workers or their technology is out of whack or whatever. They now have one way to solve their problem that is easier, quicker, and cheaper than all other ways; borrow money. Why? Here’s how it works; corporation goes to the bank, local bank. I need a 12 million dollar loan. Fine, says the bank. It takes exactly ten seconds to say fine.

It really doesn’t care why, because within minutes after we sign the papers that bank X lent 12 million dollars to company Y, bank X takes that debt, that promise that I give them to pay that debt back, and sells it to the Federal Reserve, getting fresh, new money. Who owns the actual debt? The Federal Reserve. Who’s the ultimate creditor of the American corporation? The government. Any libertarian that you encounter who tells you that the United States is split between a private sector and a public sector isn’t paying attention. There is no private sector left. Everybody is on government life support. Not just the worker getting the extra few hundred bucks in his or her check because they have no job, but every corporation.

Not just those getting the special programs for the pandemic but those that now know that the amount of money they can borrow is limitless and the interest rate just a smidgen above zero; free money, as much as you want. Therefore, you shouldn’t be surprised by this statistic; American corporations are more indebted now than they have ever been in the history of capitalism anywhere.

MEXIE: Wow.

RICHARD: It’s a story that doesn’t end well. They’re gonna be unable to pay and then the government’s gonna have to forgive their debt and then everybody else who has a debt is gonna be screaming bloody murder because my debt didn’t get — what is — and the stark favoritism to corporations over everybody else becomes more and more visible amid more and more suffering. That’s not sustainable. When the earlier question they asked about violence or revolution, that’s not because the left doesn’t have the power to force that issue. It’s just in itself breaking down. The real question should be rephrased; how far will the people who sit at the top of this system, how far will they go to hold onto it even though it’s finished?

MEXIE: Yeah. It’s gonna be a pretty scary and tumultuous fall down that we’re in for coming up. I don’t know when, but not too far off. So, Jonathan says how would a startup worker co-op compete with the global market capitalists have access to?

RICHARD: Yes, that’s a good question, Johnathan. It’s been asked for as long as I can remember. Here’s the way to answer it; not with a speculation but with a little history. The most successful worker co-op in the world at this point is this thing called the Mondragon Cooperative Corporation. It’s based in the city of Mondragon, Spain. That’s the northern part of Spain right up against the Pyrenees Mountains that separate Spain from France. It was started in 1956 by a Roman-Catholic priest, Father Arizmendi, Arizmendi by name, and he gave a famous speech to his parishioners and he said if we wait for a capitalist to come in here and hire us, we’ll all die of old age before it happens. Everybody laughed. Then he made his great suggestion; why don’t we become our own employer?

Then we don’t have to wait for some capitalist. Let’s set up a business and we will be both the employer and the employee. So he, together with six local Spanish people, started a worker co-op, 1956. So, fast-forward to 2020 right now. This corporation is the seventh-largest corporation in all of Spain. It has over 100,000 employees. They are grouped into about 200 worker co-ops under one corporate umbrella. They have competed successfully against countless capitalist enterprises. By the way, their co-ops include agriculture and industry, manufacturing and services, and everything. They’ve competed very successfully. That’s why they’ve grown like this. This kind of growth in half a century would make any capitalist proud but here is a worker co-op showing — by the way, it can go from small to very large — it can compete with capitalists and out-compete them, survive.

Many of the capitalist companies they competed with along the way couldn’t compete, went out of business, and sold their equipment to Mondragon and their workers then became also joined into the Mondragon. Here’s in a way what might be the most important point for you to understand; they’ve been so successful, they have their own bank. They’ve been so successful, they run their own university, the Mondragon University. I’ve been there. They teach courses in how to organize a worker co-op, how to finance it, how to grow it, how to deal with personnel. Imagine yourself in a business school program learning how to run businesses, only the businesses you’re learning how to run are worker co-ops, not private enterprises. Okay, they’ve done all of that. They are very, very successful.

They have their problems but they are very successful. They managed to show how to compete. By the way, it isn’t that hard. In a capitalist business, the division between the 3% at the top who run it and the 97% who don’t creates all kinds of tensions, hostilities, envy, bitterness, abuse. You know it, we know it. We know that the sexual abuse that’s been involved, that women have suffered in corporate structures forever, and all of that. You don’t have that in worker co-ops because most of them have a system of rotation, so even if you’re temporarily in a position where you’re directing other workers, you will soon be in the position that one of those you directed at is now the director and you are now the directed. So, you’re not going to do what you do — the golden rule will be everybody’s rule.

You can’t do to others what you wouldn’t want them to do to you, and they will be in that position before too long. They have a system of equality built into the enterprise whereas you have inequality built into the capitalist enterprise. It’s just, it stands to reason you’re not gonna have the same kind of experience, and that translates into productive efficiencies. The simple story; you’re a worker who’s pissed off about how you’re treated. You notice on your way out of the office at the end of the day that the light in the bathroom is still on. But it’s not your bathroom. It’s not your business. You’re hungry, you want to go home and have your dinner, so you go home. The light stays on all night. But if the business is partly yours, if you’ve been in on the meetings where you notice how much of the profit of the business is eaten up by the electric bill, you’re gonna stop.

It’s the same notion as if if it’s your home, you take better care of it than if you’re renting from somebody else. If it’s your car, you take better care of it than — I mean, maybe it shouldn’t be that way. Maybe we’ll get to a point at some point where it isn’t, but it is now. So, there are all kinds of competitive advantages that have been shown. There’s a woman, in case you’re ever interested, Virginie — it’s the French version of Virginia — Perotin, P-E-R-O-T-I-N, she’s a professor of business at the Leeds in England, Leeds University Business School. Conservative place. She’s the one who’s done the best studies. She compares businesses that are similar in almost every way except one of them is capitalist and the other one is worker co-op to see, to compare practically, empirically what the differences are.

She’s been doing this research for quite a while and she’s the leader in the world for doing this. Her results are wonderful. Capitalist enterprises do not last as long as worker co-ops. They are less efficient and less profitable. When you actually look, you see what it is your theory would lead you to reasonably expect anyway. But there’s nothing to worry about. Mondragon shows what can be done just as Emilia-Romagna does. By the way, in the Bay Area in California, worker co-ops started about thirty years ago and called the little bakery in Berkeley California the Arizmendi Bakery in honor of that Catholic priest in Spain who started it.

MEXIE: Wow.

RICHARD: That bakery is still functioning, only it’s now part of a chain of six bakeries, all of which are worker co-ops in the Bay Area. It’s another story of this successful growth and expansion of this way of doing business.

MEXIE: Wow, that’s so remarkable that Mondragon has their own university. I think that’s so powerful to be able to learn about yeah, how to democratize workplaces instead of just learning neoclassical economics or whatever.

RICHARD: Right. They have a very missionary — in the good sense of the word — missionary attitude. They want and they have people from all over the world that are interested in starting co-ops, growing their co-ops, come there to go through a real sequence of courses and studies and so forth. Now, I visited before the virus hit, so I don’t know — I assume they’ve been affected like all universities by all of this, but at the time I went, it’s a very well-developed university. Lots of equipment, it’s a very successful business as you’ll see in a minute when you go and visit, if you do, and they have a whole program to welcome visitors, to show them around, to answer questions.

So, this is a movement that’s growing and I — if I can leave you with a final thought, the 20th — the 19th and 20th century socialism was defined by the notion that the government would come in and correct or offset private capitalism, make it less harsh, make it less unequal, make it less unstable. The 21st century I think is going to go in a different direction. It looks at the 20th century and says on the one hand, great things were achieved by those socialists but also horrible things were done by those socialists. We have to learn to keep what was achieved, that was good, and learn not to reproduce what was bad. Stalin wasn’t good. That was bad. They have to face that, figure out how to handle that. All of that leads me to make a prediction which I never do, but I’m gonna make an exception.

I think that the socialism of the 21st century that we’re just beginning now will have a different focus. It’ll hold onto a notion of a government doing all kinds of things but it will be more focused on the base, on the bottom, where all of us live. It’ll be focused on bringing a radical, new universe of equality and democracy to the workplace; the factory, the office, and the store, and out of that fashion a different, better society.

MEXIE: Well, that sounds absolutely wonderful. I’m looking forward to that new paradigm being ushered in. So, sorry to Ben, Casey, and Joseph Ramirez. We didn’t quite get to your questions. Maybe another time. But just, thank you again Richard for coming on the show. This was really, really wonderful and I know that everyone got a lot out of it. So, thank you so much.

RICHARD: Very good and thank you also for coming on our show, Economic Update. We’ve had a wonderful response to it. Maybe we can keep up this nice exchange.

MEXIE: That would be amazing, yeah.

RICHARD: Take care.

MEXIE: Take care. Bye.

RICHARD: Bye-bye.

[MUSIC]

[END OF RECORDING]

(www.leahtranscribes.com)